Maps are only useful to a certain extent

The main point of the Tyner reading was that maps are useful to a certain extent, but they have their limitations. To be useful, maps must omit some details from the real world. For example, when trying to get from the UGL to the Illini Union, seeing roads, sidewalks, and landmarks is useful, but seeing steam tunnels and sea level isn’t useful.

Maps are always changing

Monmonier’s reading had a few key takeaways: maps are always changing, maps can be biased, and maps can be inaccurate. In some parts of the world — especially parts with political turmoil — maps continually change. For example, South Sudan split off from Sudan while I was taking geography in high school. Czechoslovakia split in two in 1993, into Slovakia and the Czech Republic.Although most of the change has happened on the “other side of the world,” United States maps are still changing from non-political forces. In Aug. 2018, The New York Times brought to light how a relatively small group of people can practically change the map: Google has the power to rename neighborhoods, make new neighborhoods, and define borders.

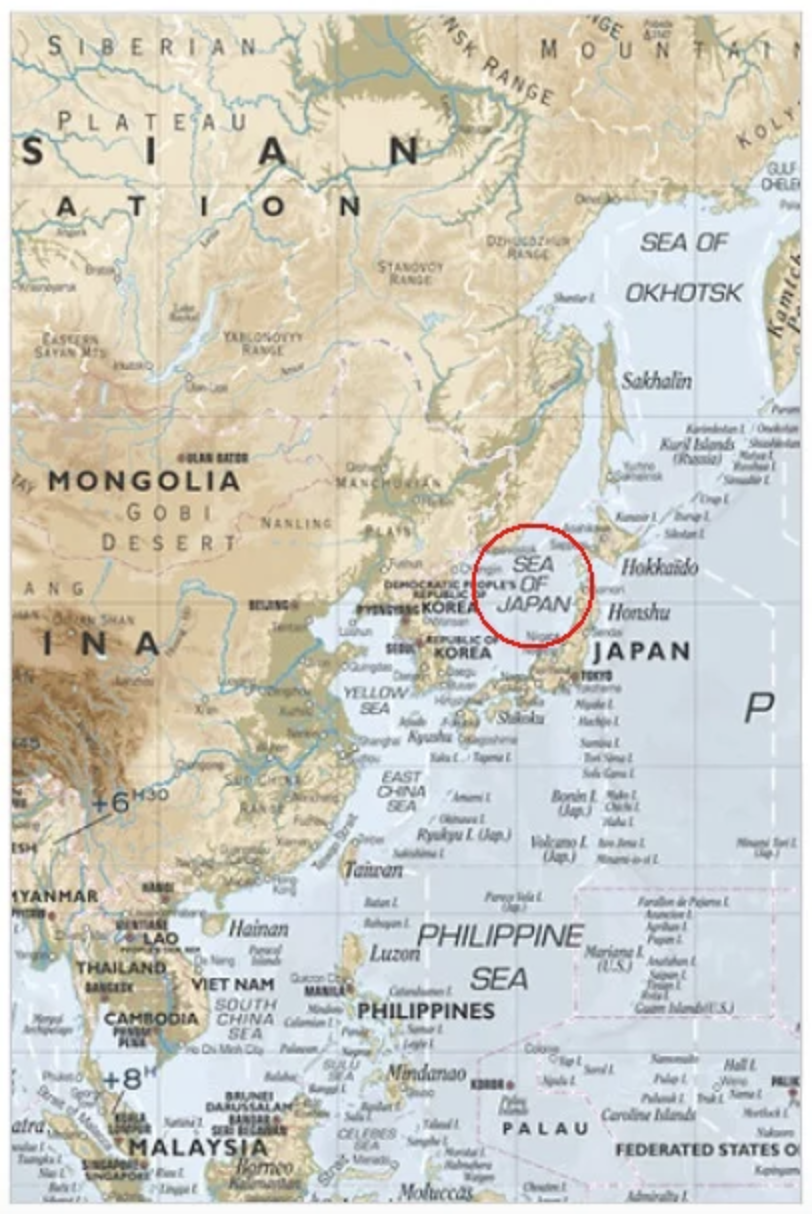

Maps can be biased

Our bias, regardless of whether conscious or unconscious, plays into how we make maps. Every time cartographers make a map, they must take a side on the Israel/Palestine controversy. On the other hand, IKEA showed its unconscious bias when it named the East Sea the Sea of Japan, which ultimately caused them to stop producing all maps when many Koreans took offense.

Maps can be inaccurate

Lastly, most maps are inaccurate. When representing a 3D world on a 2D map, we must distort reality. Below are two representations of a 2D map: the argument of the left map is that area is more important than shape, and the argument of the right map is that shape is more important than area.